How Fragmented Frontline Systems Increase Risk in Large Organizations

Learn how fragmented frontline systems increase compliance, security, and operational risks in large organizations, and how to fix them effectively.

Read more

How to Implement Fair Priority Rules at High-Volume Service Locations

Learn how to implement fair priority rules at high-volume service locations with clear steps, automation tips, and practical examples for better flow.

Read more

How to Standardize Service Processes in Multi-Location Organizations

Learn how to standardize service processes in multi location organizations to improve consistency, control costs, and strengthen operational performance.

Read more

Top 10 Visitor Management Systems for Enterprises

Compare the top visitor management systems for enterprises and find the best visitor management system to manage queues, check-ins, and visitor flow at scale.

Read more

Queue Management vs. Service Orchestration: What Enterprises Actually Need

Queue management vs. service orchestration: understand the key differences, use cases, and what enterprises actually need to run operations efficiently.

Read more

How Retail Benefits From Amazing Customer Experience

Learn how an amazing customer experience improves retail customer experience, builds loyalty, and drives better results inside the retail store.

Read more

Long Waiting Times Cost You Sales

Long waiting times and their effect on sales: why customers' boredom equals less profit for your business, and how to improve your failing queuing strategy.

Read more

4 Reasons Your Customer Service Strategy Isn't Working

Learn why your customer service strategy isn’t working and how digital customer service strategies improve wait times, staffing, and service quality.

Read more

Mistakes to Avoid When Interpreting Public Sector Service Data

Learn how to avoid common mistakes when interpreting public sector service data and improve decision-making with actionable insights for better service delivery.

Read more

How to Manage Heavy Footfall: Practical Strategies for Busy Service Locations

Learn how to manage footfall using digital queues, remote check-in, wait time visibility, and staffing strategies to reduce crowding and improve flow.

Read more

10 Best Customer Service Analytics Platforms for Public Sector Agencies

Compare the top service analytics platforms for public sector agencies to track wait times, improve staff performance, and deliver better customer service.

Read more

Top 8 Remote Sign-In Systems for High-Traffic Government Locations

Compare the top remote sign in and remote check in systems for high-traffic locations and find the best check in solution for your needs.

Read more

Pros and Cons of Using SMS Notifications for Enterprises

Explore the pros and cons of using SMS notifications for enterprises, including benefits, risks, and best practices for effective communication.

Read more

How Can QR Codes Replace Traditional Registration Completely?

Replace paper forms with QR codes for faster, contactless registration. Learn how QR code scanners streamline check-ins, reduce errors, and improve data accuracy.

Read more

How to Track and Report ROI from Queue Management Systems

Learn how to track, measure, and report ROI from queue management systems using the right metrics, benchmarks, and ROI reporting methods.

Read more

How to Choose the Right Waiting Room TV System for Your Organization

Learn how to choose the right waiting room TV system, from live queue displays to integrations, accessibility, and cost vs value considerations.

Read more

Queuing Theory as Applied to Customer Service

What are the types of customer behavior? How can you improve your customer service? These are the questions you can answer by studying queuing theory.

Read more

Queue Management System Features Your Business Needs

Discover 8 essential queue management system features that reduce wait times, improve staff efficiency, and create better customer experiences.

Read more

Tips to Optimize Online Appointment Scheduling via Visitor Websites

Learn practical tips to optimize online appointment scheduling via visitor websites and help website visitors book faster with less friction.

Read more

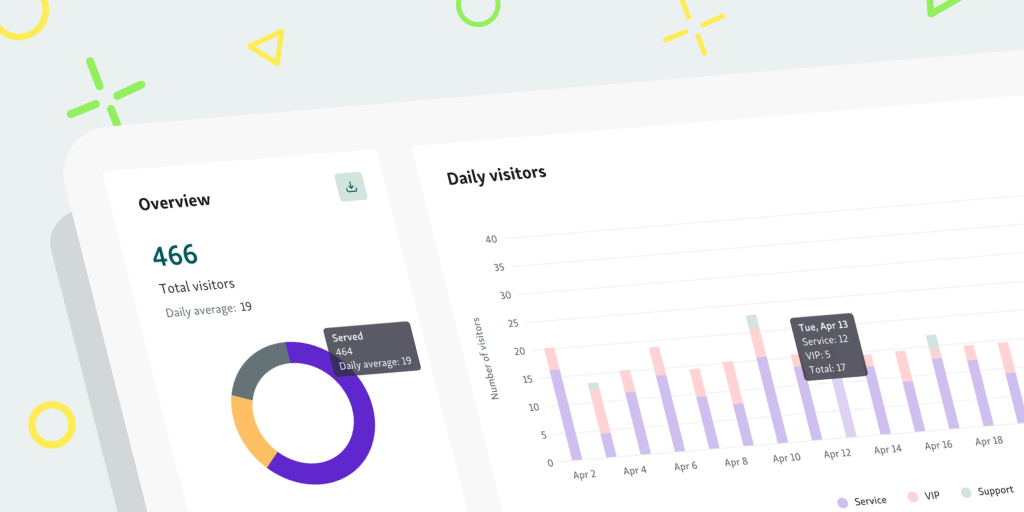

Dashboard Features You Didn’t Know Could Transform Multi-Department Workflows

Discover how dashboard features like real-time data sync, performance metrics, and automated alerts can transform multi-department workflows and improve efficiency.

Read more

Staffing & Scheduling With a Queue Management System

Learn how to optimize staffing and scheduling with queue management system insights, improve employee performance, and streamline workforce planning.

Read more

4 Ideas to Reduce Customer Service Wait Times

Learn 4 practical ways to reduce customer service wait times, improve service flow, and create calmer experiences for customers and staff.

Read more

Top 6 Data Insights You Can Gain from Appointment Scheduling Software

Discover how appointment scheduling software and data insights can optimize your operations, improve client satisfaction, and streamline your business.

Read more

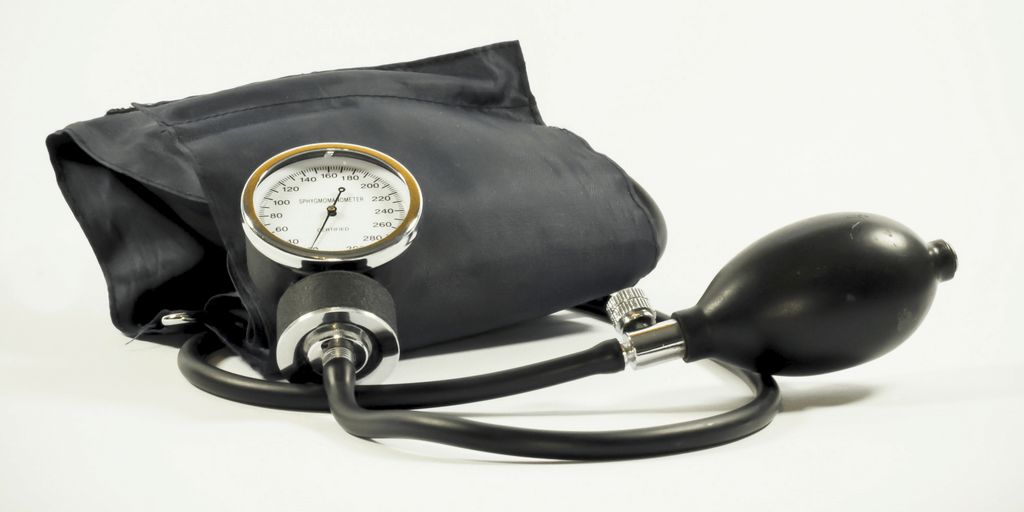

Automated SMS Alerts vs. Manual Updates: Which Works Better in Healthcare

Explore the benefits of automated SMS alerts in healthcare. Learn how they reduce no-shows, improve patient flow, and enhance staff efficiency in busy settings.

Read more

9 Must-Have Tools for Improving Customer Satisfaction in Retail Stores

Discover essential tools to improve customer satisfaction in retail stores. Learn practical ways to boost experience, streamline service, and delight shoppers.

Read more

Best Queue Management Systems in 2026

Explore the best queue management software, including Qminder, JRNI, and Qmatic. Compare features, pricing, and find the right solution for your business needs.

Read more

How Staff Can Use Remote Check-Ins to Plan Daily Operations

Learn how remote check in helps staff plan daily operations, balance workloads, reduce front-desk congestion, and improve check in flow before visitors arrive.

Read more

The Role of Personalized Messaging in Reducing Customer Wait Frustration

Personalized messaging helps reduce customer waiting time, lower frustration, and improve communication. Learn how public offices can use it to enhance service.

Read more

How Can Data Help Justify Budget Increases?

Use data to justify a budget increase with clear metrics, visuals, and ROI. Learn how evidence-driven insights strengthen budget approval decisions.

Read more

5 Common Challenges in Appointment Scheduling and How to Overcome Them

Struggling with double-bookings, no-shows, and long wait times? Learn 5 common appointment scheduling challenges and how to fix them using modern online tools.

Read more

8 Service Dashboard Providers That Simplify Operations for Public Sector

Compare the top 8 service dashboard providers for the public sector. See features, strengths, and pricing to find the right customer service dashboard for you.

Read more

Digitizing Queue Token Dispensers

Digitize your token dispenser with a digital queue management solution for faster service, virtual check-ins, and smoother visitor flow across all industries.

Read more

Comparing Manual vs. Automated Appointment Scheduling for Public Sector Efficiency

Compare manual vs automated appointment scheduling and see how automation boosts efficiency, cuts wait times, and improves citizen services in the public sector.

Read more

Top 5 Performance Metrics Every Retail Service Dashboard Should Track

Discover the top 5 performance metrics every retail service dashboard should track to enhance customer experience and operational efficiency.

Read more

Why Every City Hall Needs a Centralized Service Dashboard for Citizen Requests

Discover why a centralized customer service dashboard helps city halls speed up requests, boost transparency, and improve service delivery for every citizen.

Read more

How Retail Chains Use Waiting Room TVs to Improve In-Store Experience

Improve customer experience in retail stores with waiting room TVs that cut wait times, provide live updates, and enhance the overall in-store experience.

Read more

Top 7 Remote Check-In Systems Helping Citizens Skip the DMV Line

Explore the top remote check-in systems helping citizens skip long DMV lines with mobile queues, real-time updates, and faster, smoother service experiences.

Read more

The ROI of Queue Analytics for Enterprises

Discover how queue analytics improves conversions, staffing, and customer flow. Learn key metrics, real examples, and ROI insights for enterprise retail teams.

Read more

8 Self-Service Kiosk Platforms That Help Cut Wait Times

Explore the top 8 self-service kiosks that cut DMV wait times, speed up check-ins, and improve visitor flow for government, and public service centers.

Read more

Queue Management in Test Labs - Making Clinic Visits Safe

Improve test lab safety and efficiency with smart queue management systems. Reduce crowding, improve communication, and create smoother clinic visits.

Read more

Speed Matters: 10 Tips for Delivering Faster Customer Service

Discover 10 proven ways to deliver faster customer service, improve efficiency, and enhance customer satisfaction with actionable tips and tools.

Read more

Queue Barriers: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Discover the pros and cons of queue barriers and explore smarter alternatives like virtual queuing systems to improve flow, accessibility, and customer experience.

Read more

How Self-Service Kiosks Reduce Wait Times for Permits and Renewals

Discover how self-service kiosks and DMV self-service kiosks help reduce wait times, streamline services, and improve efficiency for permits and renewals.

Read more

How Visitor Websites Can Simplify Pre-Registration and Appointments

Discover how a visitor website simplifies the pre-registration process, automates appointments, and enhances efficiency for both visitors and staff.

Read more

Top Analytics Tools to Improve Visitor Flow in Government Buildings

Top analytics tools for visitor flow management include Qminder, Vizitor, Qmatic. Qminder tracks daily, weekly, and monthly metrics including wait times, service durations, and visitor counts.

Read more

Top 5 Ways Queue Systems Boost Workforce Productivity and Performance

Discover how flow management systems and queue systems boost workforce productivity, improve focus, and enhance service efficiency across every department.

Read more

7 Types of People in a Queue

Learn the 7 types of people in a queue and how understanding their behavior, with tools like Qminder, can improve waiting experiences.

Read more

How Remote Check-In Simplifies Visitor Management

Simplify visitor management with remote check-in. Discover how customer check-in systems and tools like Qminder improve efficiency, safety, and experience.

Read more

How to Enhance Your Customer Waiting Room Experience

Discover how to improve the waiting room experience with comfort, technology, and design strategies that enhance customer satisfaction and reduce stress.

Read more

Why Every Government Office Should Use a Service Dashboard

Discover how a service dashboard improves efficiency, transparency, and citizen trust in government offices with real-time data from tools like Qminder.

Read more

How Targeted SMS Alerts Can Cut Missed Appointments

Discover how text appointment reminder services can reduce no-shows in city services, improve efficiency, and save costs with tools like Qminder.

Read more

What is the Customer Experience Pyramid?

93% of customer experience initiatives are bound to fail. To help you understand why this happens, take a look at the customer experience pyramid.

Read more

How Patient Flow Solutions Cut LWBS and Safeguard Hospital Revenue

Discover how patient flow management reduces LWBS, improves hospital efficiency, and safeguards revenue using digital solutions like Qminder.

Read more

How to Ask Questions to Get Customer Feedback

Learn how to ask for feedback the right way. Discover effective ways to ask for feedback, avoid common mistakes, and turn responses into real improvements.

Read more

Top Benefits of Remote Sign-In for Government and Healthcare Services

Explore the key benefits of remote sign-in systems in government and healthcare, from reducing wait times to enhancing safety and operational efficiency.

Read more

How SMS Reminders Help Public Services Cut No-Shows and Delays

Discover how sms appointment reminders help city public services cut no shows, reduce delays, and improve citizen experience with simple, reliable texts.

Read more

Key Information to Include on Visitor Websites for Government Offices

Learn what website visitors expect from government office websites and how visitor websites improve queue management, service flow, and satisfaction.

Read more

Benefits of Waiting Room TVs for Queue Updates in Government Offices

Discover how waiting room TV services improve government waiting rooms with real-time queue updates, clear communication, and enhanced citizen satisfaction.

Read more

How to Choose the Best Self Check-in Kiosk for Government Departments

Learn how to choose the best self service check in kiosk for government departments with tips on features, scalability, integration, and citizen experience.

Read more

How Frontline Teams Can Drive CSAT in Government Services

Discover how frontline teams can improve CSAT in government services through better queue management, communication, personalization, and staff support.

Read more

How Service Dashboards Help Reduce No-Shows and Long Wait Times

Learn how service dashboards help organizations reduce no-shows and long wait times by providing real-time insights and improving appointment management.

Read more

Ticket-Based vs Virtual Queue Systems for City Halls and Government Offices

Compare ticket queue systems and virtual queue systems to improve wait times, staff efficiency, and citizen satisfaction.

Read more

How to Use Footfall Analytics to Improve Customer Service

Learn how to use customer footfall analytics to improve service, reduce wait times, and plan smarter with real-time data and predictive insights.

Read more

What Patient Experience Can Learn From Customer Experience

Discover how patient experience in healthcare can improve by adopting customer experience strategies like empathy, tech, and personalization.

Read more

The Power of Using Customer Names to Create Personalized Experiences

Discover how using customer names in service builds trust, improves experience, and boosts loyalty, with tips, best practices, and tools to do it right.

Read more

BOPUS and Queue Management: Improving Service Efficiency Across Industries

Learn how integrating BOPUS with a queue online system improves service efficiency, reduces wait times, and enhances customer experience across industries.

Read more

The Long-Term ROI of Implementing Efficient Queue Management in Public Sector Agencies

Discover how queue management systems boost efficiency, improve citizen satisfaction, and deliver long-term ROI for public sector agencies like DMVs and city halls.

Read more

Retail Checklist: Tips for Managing Crowds on Black Friday

Black Friday brings massive crowds and long lines. Use this retail checklist to manage traffic, staff, and store operations for a smooth shopping experience.

Read more

7 Self-Service Kiosk Platforms That Speed Up DMV Lines

Discover 7 top self service kiosk DMV platforms to reduce wait times, streamline check-ins, and improve efficiency for staff and visitors alike.

Read more

10 DMV Technologies That Actually Reduce Wait Times

Discover 10 DMV technologies that reduce wait times, improve citizen flow, and streamline services. Learn how tools like Qminder make DMV visits faster.

Read more

20+ Best Patient Queuing Software

The best patient queuing software includes Qminder, known for HIPAA compliance and virtual queuing, Vizitor, and Curogram and more.

Read more

How Exceptional Customer Experiences Improve Patient Satisfaction in Hospitals and Clinics

Discover effective strategies to improve patient satisfaction in hospitals and clinics, boost trust, and enhance overall healthcare experiences.

Read more

Creative Ways to Use Waiting Room TVs Beyond Queue Management in Local Government Offices

Discover creative ways to use waiting room TV software in government offices to engage citizens, share updates, and enhance the overall waiting experience.

Read more

Using Historical Data to Predict Queue Patterns and Improve Operations in Public Services

Learn how public services can use historical queue data to predict patterns, optimize operations, and improve citizen experience with smarter staffing & processes.

Read more

The Hidden Challenges of Ticket-Based Queue Management in Public Sector Agencies (And Why Virtual Queues Are the Future)

Discover the hidden drawbacks of ticket queue management systems in public sector agencies and learn why virtual queues are the smarter, modern solution.

Read more

Customer Service – To Automate, or Not to Automate, That Is the Question

Discover the pros and cons of customer service automation, key questions to ask, and how Qminder can help balance automation with human support.

Read more

5 Reasons Why Your Customers Leave Your Business

Discover the 5 key reasons why customers leave your business and learn how to prevent customer attrition with actionable insights and effective strategies.

Read more

5 Easy Ways to Modernize Patient Waiting Room Experience

Improve the patient waiting room experience with simple changes that reduce stress, boost flow, and support staff. Learn how tools like Qminder can help.

Read more

How To Use Customer Behavior Data to Improve Service Efficiency in Government Agencies

Learn how to use customer behavior data to improve public services, reduce wait times, and deliver more personalized experiences with the right tools.

Read more

Strategies to Deliver Personalized Experiences in Retail Click-and-Collect Services

Learn simple, practical ways to improve the retail pickup experience using tools like smart check-ins, messaging, queue updates, and customer feedback.

Read more

The Best Alternative Solutions for a Take-a-Number System

Explore smarter alternatives to the take-a-number system. Learn how virtual queues, scheduling, and messaging tools improve service and reduce wait times.

Read more

The Role of Customer Journey Mapping in Enhancing Citizen Satisfaction in Public Services

Discover how customer journey mapping helps public agencies improve citizen satisfaction by fixing service gaps, streamlining steps & improving communication.

Read more

How Queue Management Systems Use Multi-Location Insights to Improve Staff Efficiency

Discover how multi-location insights help improve staff efficiency, service quality, and queue management across branches with one simple dashboard.

Read more

Waitlist Monitor: What It Is and How It Works

A waitlist monitor or a waiting room tv is a digital screen that shows real-time updates on the customer queue.

Read more

What Customer Journey Mapping Is and How to Create it

Learn what customer journey mapping is, how to create one, and how it helps public services improve citizen satisfaction across every service touchpoint.

Read more

Customer Satisfaction Metrics You Need to Be Tracking

Learn the top customer satisfaction metrics, how to track them, and how to use the insights to improve service quality and build long-term customer trust.

Read more

How to Reduce Bottlenecks and Improve Customer Flow in Public Sector Agencies with Customer Flow Management System

Discover 7 smart strategies to reduce bottlenecks and improve customer experience flow in public sector services with a customer flow management system.

Read more

How to Choose a Queue Management System?

Looking for the best queue management system? Discover how to choose the right one and explore top tools to improve customer experience and reduce wait times.

Read more

How Service Intelligence Helps You Run a Smarter Business

Learn how service intelligence helps businesses improve wait times, staff performance & customer service across all locations with real-time, actionable data.

Read more

Best Practices for Managing High-Demand DMV Services

Discover best practices for managing high-demand DMV services. Learn how to enhance the DMV experience with smarter workflows and DMV online services.

Read more

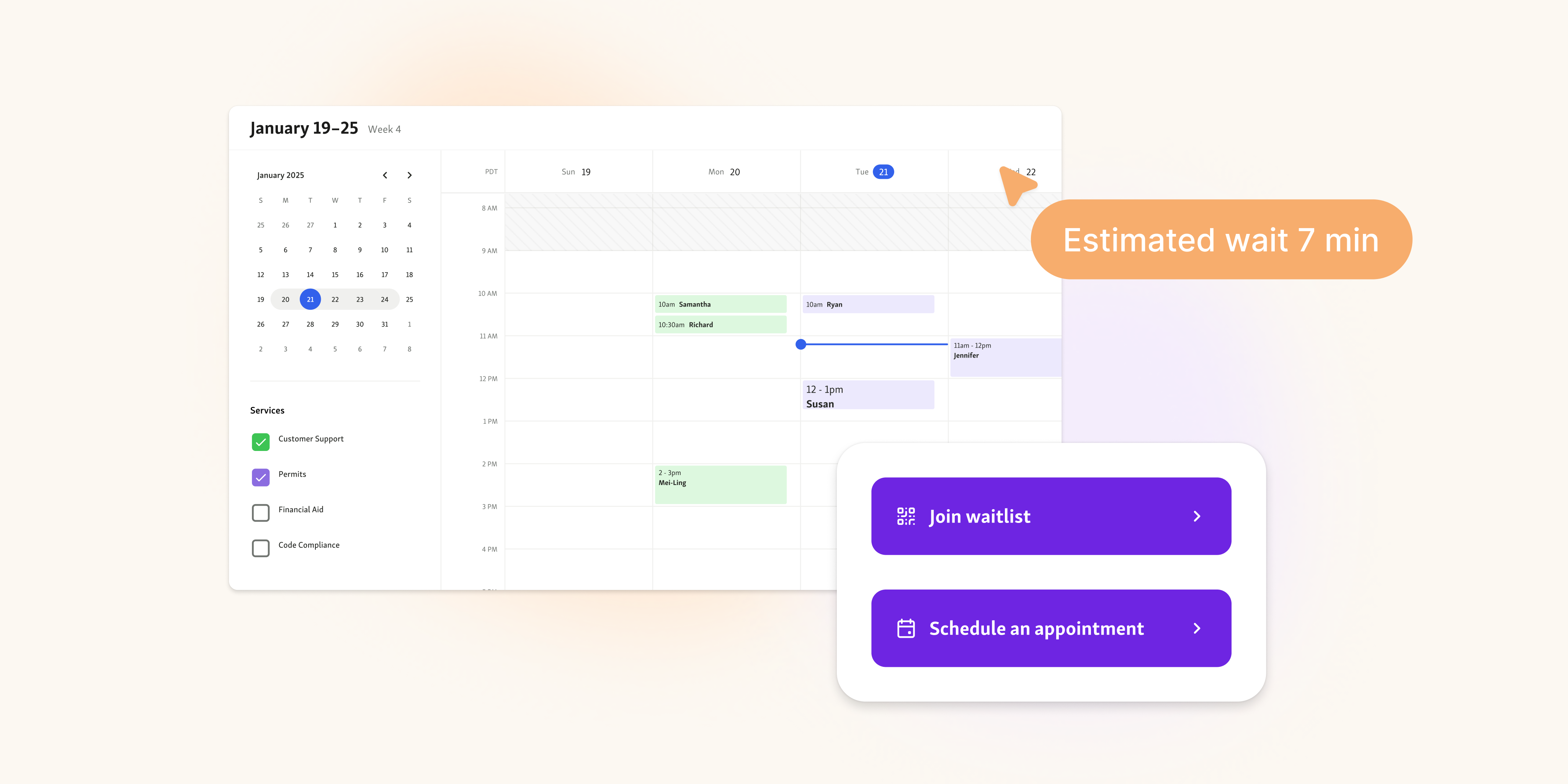

Appointments Is Here: A New Chapter for Visitor Management

Offer scheduled visits alongside walk-ins! Appointments brings structure, clarity, and control to your daily service flow.

Read more

The Best and Worst Times to Visit a Hospital: A Guide to Minimizing Wait Times

Learn the best and worst times to visit a hospital, what affects Patient Waiting Times, and how tools like Qminder help reduce waiting time and stress.

Read more

Why Are Hospital Wait Times in Canada So Long?

Discover why hospital wait times in Canada are so long. Explore key challenges, impacts, and how better queue management can improve the healthcare experience.

Read more

5 Ways to Enhance Customer Experience in Government Services Like DMVs and City Halls

Discover 5 proven ways to improve customer experience in government services like DMVs and city halls, with tips to reduce waits and boost satisfaction.

Read more

The Beginner’s Guide to Queuing theory

Learn what queuing theory is, why it matters, and how it applies to real-life services—from retail to healthcare. A simple, human-friendly beginner’s guide

Read more

7 Key Strategies for Efficient Resource Allocation in Local Government Services

Learn 7 practical strategies to improve resource allocation in local government services. Boost efficiency, manage demand, and deliver better public service.

Read more

How to Improve Customer Communication With SMS Text Messaging

Learn how to improve customer communication with SMS. From real-time updates to feedback collection, discover why Qminder is the tool your team needs.

Read more

5 Reasons Virtual Queues Are Essential for Local Government Services Like DMVs and City Halls

Learn why a DMV virtual queue is essential for local government offices. Cut wait times, ease stress, and improve service with a smart virtual queuing system.

Read more

Improving CSAT in Local Government Services: Effective Strategies and Tools

Discover how local governments can improve CSAT with better queue management, real-time feedback, and citizen-focused service tools like Qminder.

Read more

Introducing Appointments: Now Scheduling the Future of Queuing

Qminder Appointments is here: offer scheduled visits alongside walk-ins, streamline service, and manage both flows in one place.

Read more

Are Walk-Ins More Efficient Than Appointments?

Are walk-ins more efficient than appointments? Learn the pros, cons, and how queue systems like Qminder help manage both for smoother hospital operations.

Read more

How Local Governments Can Use Data-Driven Insights to Improve Queue Flow and Citizen Satisfaction

Discover how local governments can use data-driven insights to improve queue flow management and boost citizen satisfaction in city halls, DMVs, and beyond.

Read more

Best Practices for Managing Customer Flow in High-Traffic Government and Public Service Environments

Struggling with long lines and crowded lobbies? Learn best practices and tools for effective customer flow management in government & public service settings.

Read more

7 Strategies to Optimize Patient Flow in Healthcare

Learn how to optimize patient flow in healthcare using digital tools like self check-in kiosks and queue systems to reduce delays and improve care delivery.

Read more

HIPAA & SOC 2 Compliance in Digital Queue Systems: Best Practices for Secure Operations

Ensure secure operations with HIPAA & SOC 2-compliant digital queue systems. Learn best practices to protect sensitive data in clinics and public offices.

Read more

How Queue Systems Can Improve Customer Experience and Reduce the Effects of Waiting in Healthcare

Discover how modern queue systems help hospitals reduce wait times, boost patient satisfaction, and streamline operations for better care delivery.

Read more

Virtual Queuing: A Complete Guide to Virtual Queue System

Virtual queue management systems improve wait times, boost efficiency, and enhance service. Learn how Qminder is the ideal solution for your needs.

Read more

How Investing in Self-Service Kiosks Helps Queuing

Discover how self-service kiosks improve queuing, boost efficiency, reduce wait times, and enhance customer experience across industries.

Read more

Single-Line Queues Vs Multiple-Line Queues: Which One Is Better?

Single-line queues vs multiple-line queues: which is better for managing customers? Let's talk about the pros and cons of single and multi-line queues.

Read more

How to Reduce Patient Wait Times in Hospitals

Reduce patient wait times with queue management and appointment scheduling that streamline check-ins, balance walk-ins, and optimize staff efficiency.

Read more

Key Factors That Affect Service Time in Government Services and How to Manage Them

Discover key factors that affect service time in government offices and learn how tools like Qminder help improve efficiency, satisfaction, and staff workflow.

Read more

Queueing Theory vs. Practical Queue Management: What Public Sector Agencies Can Learn

Discover how queuing theory compares to practical queue management in the public sector. Learn how real tools improve service delivery, efficiency & satisfaction.

Read more

Why Hospital Wait Times Are So Long

Discover why hospital wait times are so long and explore smart strategies to reduce delays, improve patient flow, and enhance the overall care experience.

Read more

What Are Self Check-in Kiosks and How Can They Improve Service Efficiency in Local Government?

Discover how self check-in kiosks streamline citizen services in local government, reduce wait times, and boost staff efficiency with real-time digital tools.

Read more

Why Your City or Government Department Should Switch to a Paperless Queue System

Discover why your city or government department should switch to a paperless queue system. Improve wait times, efficiency, and citizen satisfaction today.

Read more

How Appointment Scheduling Systems Enhance Customer Experience in Government Services

Discover how appointment scheduling systems like Qminder help local governments reduce wait times, boost accessibility, and improve public service delivery.

Read more

How Appointment Scheduling Reduces Administrative Burden in Local Government Agencies

Discover how appointment scheduling software helps local government agencies cut admin workload, streamline citizen services, and improve efficiency.

Read more

7 Features to Look for in Appointment Systems for Local Government Services

Learn how automated appointment scheduling in public offices boosts efficiency, reduces wait times, and improves customer satisfaction.

Read more

The Problem With Government Office Wait Times And How to Solve It

Struggling with long wait times in government offices? Discover the causes, impact, and smart solutions like Qminder to streamline the visitor experience.

Read more

10+ Best Waitlist App and Software [Updated 2026]

Discover the top waitlist apps in 2026 for restaurants, healthcare, and retail. Compare features and pricing to find the best fit for your business needs.

Read more

Why Automated Appointment Scheduling is Key for High-Volume Services in Public Offices

Learn how automated appointment scheduling in public offices boosts efficiency, reduces wait times, and improves customer satisfaction.

Read more

7 Ways Personalized Service Can Transform Customer Satisfaction

Discover 7 powerful ways personalized service can boost customer satisfaction, build loyalty, and set your business apart in today’s competitive market.

Read more

The Benefits of Appointment Scheduling Software in DMV and City Hall

Discover how appointment scheduling software can improve efficiency, reduce wait times, and enhance citizen satisfaction in government offices.

Read more

7 Best Appointment Scheduling Tools for Citizen Engagement in Public Services (2025)

The best government appointment scheduling softwares are Qminder, Acuity Scheduling, Setmore, Square Appointments & Appointy.

Read more

How Improving Citizen Flow Can Deliver Measurable ROI for Local Governments

Optimize citizen flow can deliver measurable ROI by lowering operational costs and enhancing resource allocation.

Read more

Maximizing Customer Satisfaction in Local Government Offices with Appointment Scheduling Tools

Learn how appointment scheduling tools can enhance efficiency, reduce wait times, and improve customer satisfaction in local government offices.

Read more

Understanding FIFO: First-In, First-Out in Queue Management

Learn about FIFO queue management, its benefits, and how it improves customer satisfaction, operational efficiency, and service fairness across industries.

Read more

Customer Satisfaction – Make Your Customer Addicted to Your Business

Improve customer service with cost-effective solutions, streamline operations, and boost loyalty by addressing common challenges with modern technology

Read more

Top 10 Qless Alternatives for a Queue Management System

Discover the top 10 Qless alternatives for effective queue management systems, designed to enhance customer experience, reduce wait times, and improve efficiency.

Read more

9 Best Strategies to Reduce No-Shows

Struggling with patient no-shows? Discover 9 actionable strategies to reduce missed appointments, improve attendance, and enhance patient experience.

Read more

How Queue Management Software Helps Government Offices

We associate public service with long wait times, but it doesn't have to be this way. A digital queue system can set things right for government offices.

Read more

What is Customer Experience and Why is It Important in the Government Sector?

Discover why customer experience is crucial in the government sector, how it impacts public trust, and how better service delivery improves citizen satisfaction.

Read more

Queue Management Systems: Cost vs. Benefits Analysis for Public Sector Agencies

Reduce wait times and improve efficiency with a queue management system. Explore the cost vs. benefits for public agencies & how the right system enhances service.

Read more

How Virtual Queuing Can Solve the DMV’s Long Wait Times

Reduce DMV wait times with virtual queuing. Discover how digital solutions improve efficiency, customer experience, and streamline operations for better service.

Read more

Walk-in vs. Appointment Scheduling: Choosing the Best Approach

Explore the pros and cons of walk-ins vs appointment scheduling & how the right approach with appointment queue management software can enhance business efficiency.

Read more

Local Government Software Solutions: ERP, CRM, Accounting & More

Discover cutting-edge local government software solutions designed to streamline operations, enhance efficiency, and empower your community.

Read more

Public Sector Customer Service: Challenges and Best Practices

Discover effective strategies to transform public sector customer service and enhance citizen engagement in this comprehensive guide.

Read more

Government Customer Experience: Challenges & Best Practices

Explore the importance of government customer experience, key challenges, and effective strategies for comprehensive CX improvement and success.

Read more

Why Does the US Government Move So Slowly (Quick Answer)

Explore why the US government moves so slowly and learn how factors like partisan politics, regulatory hurdles, and public expectations shape decision-making.

Read more

Federal Agency Customer Experience Act: Key Insights & Impacts

Discover how the Federal Agency Customer Experience Act is reshaping government services and boosting public satisfaction with better CX standards.

Read more

What is GovTech? Benefits + Strategies Explained

Discover what GovTech is, how it's transforming government services, and the challenges and opportunities it brings for modern governance.

Read more

Government Data Analytics: Types, Applications, and Tools

Discover how Government Data Analytics transforms public services with insights into tools, strategies, and best practices for data-driven governance.

Read more

Limited English Proficiency (LEP): Best Practices & More

Discover the challenges faced by individuals with limited English proficiency and explore effective solutions to enhance communication and service delivery.

Read more

Qminder Secures €3M Seed Funding to Revolutionize Service Flow Management

Qminder, a service flow management tool for government entities like city halls, secures €3M in seed funding to enhance customer experience.

Read more

How to migrate to Qminder from Qless

Qminder is the best alternative to Qless! Check our guide on how to migrate your Qless queuing system to Qminder. Set it up in minutes.

Read more

32 Best Virtual Queue Systems – Free & Paid

See the best free and paid virtual queuing systems including queue management features such as remote check-in, notifications, and more.

Read more

Top 5 Qudini Alternatives for a Queuing System

Check the latest list of best Qudini and Veriny alternatives for walk-in visitor queue management systems and appointment booking.

Read more

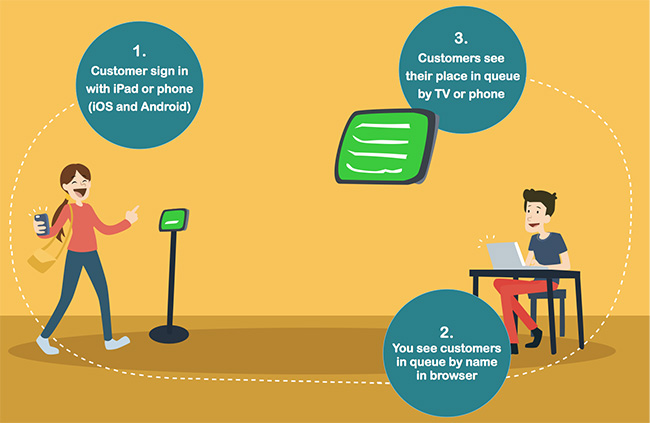

What is Queue Management System? A Definitive Guide

This is the ultimate guide to queue management and queuing systems. Learn more about queue management and the benefits of a queue management system.

Read more

4 Strategies to Reduce the Turnover Rate Among Medical Receptionists

Understand the cause of high turnover in healthcare and apply these strategies to improve staff satisfaction at your medical front desk for medical receptionists.

Read more

5 Reasons Why Hospital Queues Are So Long

Ever wondered why it takes you a lot of time to receive treatment in a hospital? Here are 5 reasons why hospital queues are so long and how to fix them.

Read more

The Importance of Greeting Your Patients

First impressions matter. All it takes to improve hospital experience is to treat your patients with respect, by greeting them using their first name.

Read more

A Guide to Implementing Queue Management Systems

Learn how to implement the different types of queuing systems such as virtual queuing, take a number machine, and self-check-in kiosks. Check the queuing systems’ pricing and hardware requirements before you decide.

Read more

The Ultimate Waiting Room Checklist: 65+ Ways to Enhance Your Space [PDF]

Download Qminder's ultimate checklist for 65+ tips and best practices on how to improve the waiting room experience in 2023.

Read more

7 Powerful Customer Service Phrases to Use

This is a list of 7 powerful customer service phrases. Learn how to make a positive impact on customer experience with these simple words.

Read more

The Effect of No-Show Appointments on Patients and Hospitals

This is an in-depth article about the effects of no-shows on healthcare. Learn how missed appointments cost hospitals 150 billion dollars a year and how to reduce the no-show rates.

Read more

4 Levels of Customer Loyalty: How to Keep Your Clients

This is a guide to customer loyalty. Find out the four stages of customer loyalty and learn the steps you need to take to improve customer satisfaction.

Read more

The Language of Queuing: Correct Etymology, Definition, and Uses

Is is "queue" or is it "que"? Is it "in line" or is it "on line"? Find out the correct etymology, usage and definition of queuing terms.

Read more

What Is a Queuing System? Definition, Examples, and Benefits

What is a queuing system and does your business need one? This is a guide to virtual queuing systems that provides examples of queue systems.

Read more

7 Common Customer Service Phrases to Avoid

This is a list of 7 customer service phrases to avoid when talking to customers. Learn which customer service phrases you should never say.

Read more

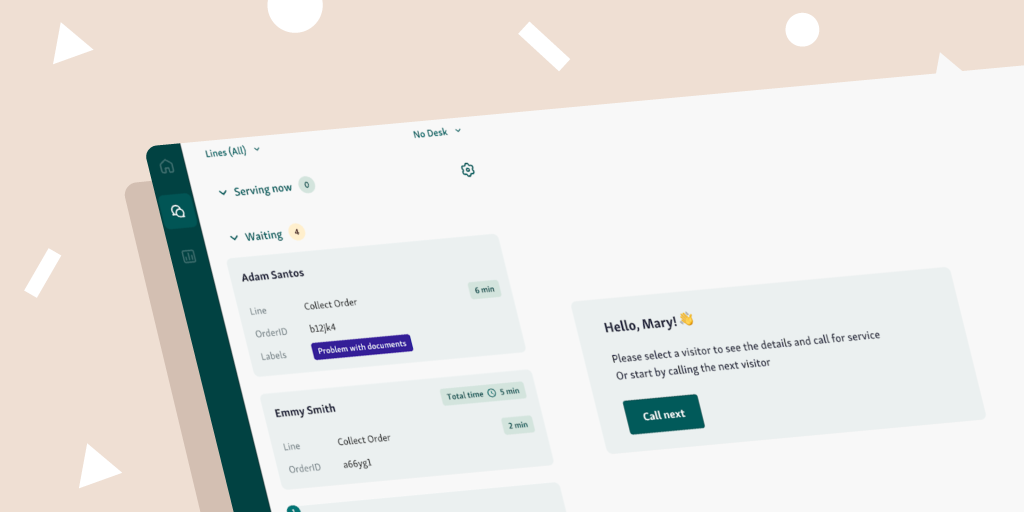

Introducing Qminder's New and Improved Service View

We've updated Qminder's Service New and introduced exciting new features. Learn about the upcoming changes and the process behind their design.

Read more

Why You Should Listen to Your Customers (And Why You Shouldn’t)

This is an article on how listening to customers improves the experience and benefits your business. Learn why you both should, and shouldn't, listen to your customers.

Read more

11 Ways to Make Customers Fall in Love With Your Brand

How do you make customers fall in love with your business brand? This guide will help you increase customer engagement and loaylty.

Read more

Back in the USSR: The Art of Soviet Queues

You think you have it bad with long queues? Let's go a few decades back, to the Soviet Union bread lines. Today's essay is "Customer service in the USSR".

Read more

Free Sign-Up & Sign-In Sheet Templates [PDF]

Download free, printable sign-in sheet and sign-up templates. Get medical, visitor, event and student sign-up sheets in PDF.

Read more

70 Customer Service Quotes to Keep You Inspired

This is a list of 70 inspirational and motivational quotes about customer service. Get inspired by these excellent customer service quotes, sayings and proverbs.

Read more

7 Insanely Powerful Strategies to Manage Customer Wait Times

This is a beginner's guide to managing customer wait times. Learn these 7 useful service strategies to reduce waiting times for your customers.

Read more

Make Your Event Successful With a Queue Management System

An event queue management system helps organize public events and manage in-person attendees. Coordinate a successful event with a virtual queuing system.

Read more

It’s Official: Qminder Is SOC 2 Type II Compliant

Qminder takes your data privacy seriously, and we've got SOC 2 Type II certification to prove it.

Read more

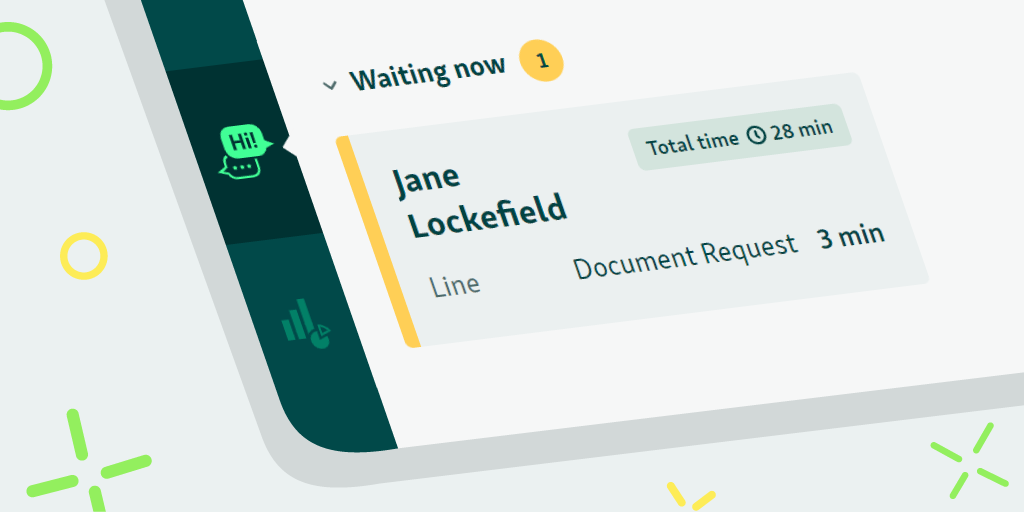

Qminder Introduces Total Time for the Service View

Qminder introduces Total Time — a brand new time indicator that helps prioritize customer for the ultimate fair queuing experience.

Read more

Improving Service Intelligence With Qminder’s Latest Update

Qminder brings you new and improved service intelligence with our latest batch of product updates.

Read more

Happy Birthday! Qminder Turns 10 Years Old

Qminder turns 10 years old! Join us 'round the bonfire as we share the stories of how Qminder came to be.

Read more

Scan COVID-19 Vaccine Certificates With Qminder

Improve customer experience by letting customers self-scan their COVID-19 vaccine certificates and COVID passes.

Read more

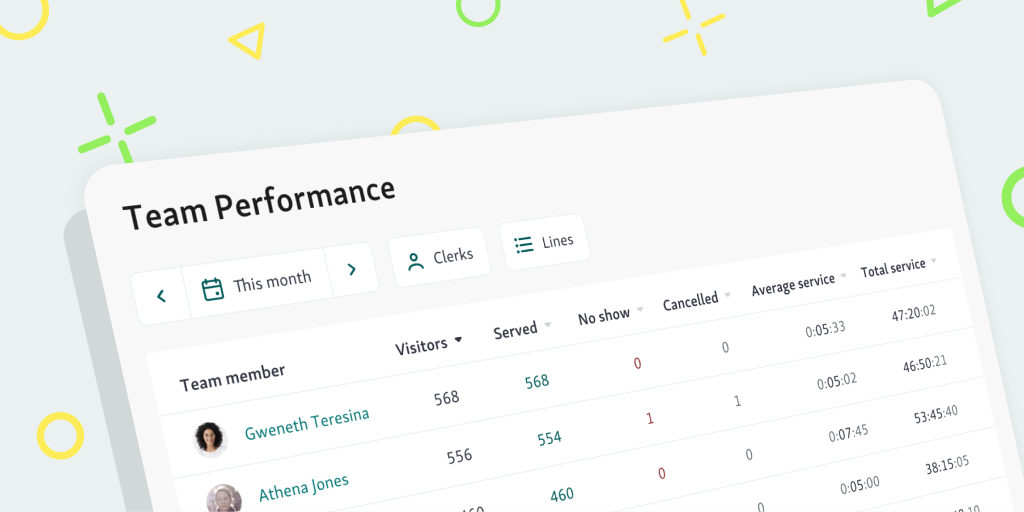

Improving Performance Tracking With Our Latest Update

The latest Qminder update brings you the improved Team Performance page, to help you assess team's effectiveness and guide your decisions.

Read more

How McDonald’s Self-Service Kiosks Changed the Customer Experience Game

McDonald's invested in self-service technology to achieve even greater profitability. Learn how to benefit your business with self-service kiosks.

Read more

Consumer Behavior During and After Pandemic: 4 Trends to Watch

One of the casualties of the coronavirus pandemic was consumer behavior. It has changed in both major and subtle ways that businesses need to account with.

Read more

Introducing New Visitor History

Qminder's Visitor History has just got a new upgrade! Manage your visitors even faster with newly-improved dashboard.

Read more

Optimizing Business Through Smart Queue Management Analytics

Queue management isn't really about waiting lines; it's about data. Data provided by queuing solutions can help you optimize your business.

Read more

60+ Queue Management Facts and Statistics You Should Know

The most relevant queue management statistics and facts 2021. A regularly updated list of facts and numbers on queuing and customer experience.

Read more

Building Great Queue Management: A Step-by-Step Guide for Any Business

Queue management is something that a lot of companies do, but few excel at. Join the ranks of the latter with our step-by-step guide to great queuing.

Read more

Patient Journey Mapping: Making Healthcare Experience Better for All

Patient journey mapping is a way of visualizing the service experiences of patients over time. Here's why hospitals and clinics should use it.

Read more

The World's Most Famous and Longest Queues

The history of the world has known many long queues, but only few get the unfortunate honor to be called The Longest Queues Ever. And here they are...

Read more

Qminder Introduces Improved Google Sheets Integration

Qminder's improved Google Sheets integration enhances customer data analytics, giving you tools for more accurate service decisions. See how to upgrade now.

Read more

9 Proven Benefits of Online Queue Management Systems

From reducing wait times to boosting revenues, there are a lot of benefits of using a queue management system. Here are 9 biggest benefits.

Read more

10 Lessons From Qminder’s Remote Work Trip to Georgia

Ever wondered what it's like to work remotely? Before becoming a digital nomad, consider reading our remote work guide, based on our experiences in Georgia.

Read more

How to Train Service Staff for Peak Hours

Does your staff have everything it needs to provide great service? What about during peak times? Learn what you can do to make your staff's life easier.

Read more

Using the Data From People Counters to Boost Service

People counters help measure footfall, i.e. the number of visitors, but they also help you measure the effectiveness of your customer service strategy.

Read more

The Cost of Queues: How Improper Queue Management Affects Your Bottom Line

Time for some queuing theory: what is the cost of waiting in customer service? You'd be surprised how much revenue you miss out on by not fixing queues.

Read more

Weighing the Options: Can Queue-Jumping Be Fair?

Just imagine: you're standing in line for hours and as your turn is coming, somebody jumps in. Is queue-jumping ever called for? You may be surprised...

Read more

How to Successfully Merge Offline and Online

What's the difference between offline and online, and which one is better? Today we're joined by Larry Kim, who gives tips on merging offline and online.

Read more

5 Key Takeaways From the X4 Conference

The X4 experience management conference organized by Qualtrics gathers the world's leading experience experts under one roof. Here are 5 lessons from it.

Read more

Deliver Wow Customer Service: 5 Ways to Improve Waiting Experience

It's the experience economy, and your customers want you to "wow" them. Even waiting experience is greatly improved through wow customer service.

Read more

7 Japanese Words That Teach Great Customer Service

What do we know about Japan? Anime, sushi, samurai, Kurosawa, and... customer service! Learn these 7 Japanese words to master their customer service craft.

Read more

11 Queue Strategy Tips, Explained in Fewer Than 140 Characters

Of what use are the tips that are so long, you can't even memorize them? Here are 11 queue strategy tips that can fit in a single Twitter post.

Read more

The Periodic Table of Customer Service Elements

Customer relationship, like all relationships, is built on chemistry. In today's class, we are looking at the periodic table of customer service elements.

Read more

6 Customer Experience Trends in Healthcare

Patient experience becomes more and more important. To help serve patients better, take a look at six main customer experience trends in healthcare.

Read more

Customer Experience Vs. Product: What's More Important?

Customer experience versus product: what should you invest in to get the most bang for your buck? CX is increasingly more relevant to business success.

Read more

A Gentleman's Guide to Queuing Etiquette

Queues are already stressful, so why needlessly escalate the tension? Learn proper queuing manners, with A Gentleman's Guide to Queuing Etiquette.

Read more

How Nike Can Help Brick-and-Mortar Survive the E-commerce Wave

Nike's famous slogan is the kind of advice that can be applied to almost any situation. Even when improving the customer service, you've got to Just Do It!

Read more

The CEO Guide to Customer Experience

Customer experience is not just some extra value you give to customers; it's a philosophy you need to adopt. Even as a CEO, you need to understand CX.

Read more

Happy Employees Make Happy Customers

Every business owner wants to make customers happy, but aren't you forgetting about someone? Employees need some love too if you want to achieve success.

Read more

25 Most Important Customer Experience Statistics

Numbers may not tell the entire story, but to understand the importance of customer experience, you need to know these customer experience statistics.

Read more

The Key to Succeeding Like an Apple Store

You're only as good as your teacher, so who better to learn retail success from than Apple? It's not about product anymore, it's about customer experience.

Read more

Creating a Customer Empathy Map

Understanding your customers is a long, exhausting journey. And just like any other journey, you can't take this one without a map — a customer empathy map.

Read more

8 Customer Service Lessons You Need to Learn

There's no shortcut to implementing great customer service, but there are shortcuts to learning about. Take a look at 8 important customer service lessons.

Read more

Personalized Customer Experience in Retail

Nobody enjoys cold, impersonal customer service. In the age of individuality and diversity, personalization is a key aspect of good customer experience.

Read more

Self-Service as the Future of Customer Service

If you want to do something right, you have to do it yourself — that's the idea behind self-service, an increasingly important part of customer service.

Read more

5 Customer Experience Mistakes to Avoid

Understanding what your customer want is not only about what to do, but also what not to do. Here are top 5 customer experience mistakes you ought to avoid.

Read more

7 Customer Retention Strategies That Really Work

Getting customers is one thing, but how do you retain them? Customer retention is no easy task, unless you try these 7 tested and proven strategies.

Read more

9 Healthy Habits of Customer Service Agents

Customer service is something you can always get better at. As long as you stick to these healthy habits of customer service, you should enjoy success.

Read more

The Future is Here — New Qminder Feature

Greeting customers is important but also tedious. If only there was someone to do it for you... No worries, your savior is here — and his name is Steve.

Read more

7 Ways to Make Customers Happy With Your Writing Skills

Is writing important to customer service? If you don't want to scare potential customers away, you need to learn this 7 valuable writing skills.

Read more

How to Show Empathy to Customers

Can empathy be taught? Only if you're willing to put yourself in your customer's shoes. Empathy begins with understanding another person's perspective.

Read more

How to Train Your Employees in Customer Service

"Customer service is important" is not something that needs to be explained. What needs to be done, however, is training your employees in customer service.

Read more

Why You Hate Waiting in Line

Do you hate queues? Well, get in line! Though hating queues is natural, people don't usually address why they feel this way about waiting. Let's find out.

Read more

37 Stats You Didn't Know About Customer Service

Ever wanted to tell someone about the importance of customer service but didn't know how? Our handy guide with 37 quick stats about CX has got you covered!

Read more

8 HIPAA Myths, Explained and Debunked

HIPAA is surrounded by many misunderstandings and myths. Why don't we debunk some of them? Welcome to the first episode of Mythbusters: the HIPAA edition!

Read more

Qminder Is Now HIPAA-Compliant

Now that Qminder is HIPAA-compliant, the question is... What is HIPAA? It's something we need to explore to explain how it may benefit your business.

Read more

How to Reduce Queues in Banks

Nowhere are queues more apparent and aggressive than in banks. But the solution to this poor customer service epidemic is easier than you may think...

Read more

Why the Other Line Always Moves Faster Than Yours

Have you ever felt the other queues moved faster than yours? Are you just that unlucky or is it a trick of your mind? Let's get to the bottom of this...

Read more

Qualities of Good Queue Design

Modern times are all about good, sleek design. Queue management is no different: designing your waiting experience is a crucial step towards success.

Read more

How to Manage Queues in Restaurants

"Stay hungry" is a good slogan for startups, but not your restaurant. Without queue management, you risk losing clients after making them wait for too long.

Read more

Why Great Customer Service Begins With a Smile

There's no better way to know that your customer service is working than see your customer smile. But should you too turn your frown upside down?

Read more

5 Easy Steps to Better Waiting Line Experience

Every customer wants to have a better waiting line experience. But what steps you need to take to provide them with this experience? Tune in to find out.

Read more

12 Dos and Don'ts of Effective Queuing

Queuing would be so much easier if there was a list of rules on what (not) to do. Oh wait, there it is — our manual for effective customer queuing.

Read more

Disney and the Art of Queuing

As an entertainment empire, Disney knows a thing or two on how to keep customers happy and engaged despite long wait times. Take a cue from the Big Mouse.

Read more

How the In-Store Customer Experience Affects the Bottom Line

The in-store customer experience can make or break a business. Learn how you can drive more sales and get customers to return with these tips.

Read more

What It Means to Be Customer-Centric

What does it truly look like when you put your customer first? What customer wants and what you want is not mutually exclusive when you're customer-centric.

Read more

Customer Feedback as a Way to Great Customer Experience

For a business, nothing is more valuable than customers leaving honest feedback about service. Customer feedback is the best way to evaluate your success.

Read more

Why Schools Need Queue Management

From enrollment to admission office, schools have problems with managing queues. Can a queuing solution help with that? It's time for a lesson on queuing.

Read more

The Impact of Poor Customer Service on Retail

89% of consumers stop doing business with a company due to bad customer service. Still think you can keep ignoring the impact of poor customer service?

Read more

Qminder Wins Awards from FinancesOnline

Qminder wins two awards from FinancesOnline - one of the biggest B2B and SaaS review platform. With our exceptional UX, we won the hearts from both our own customers and from the reviewers.

Read more

The Psychology of Queuing As a Key to Reducing Wait Time

How to reduce wait time for your customers? First, understand the psychology of queues. There are a lot of unspoken rules about queuing...

Read more

How to Reduce Anxiety in Your Patients

Wondering how you can reduce anxiety in patients? Here are some easy ways to improve patient experience and reduce patient anxiety.

Read more

What Are the Worst Times to Visit a Hospital?

What are the worst times to visit a hospital? Just like retail, hospitals can experience an overflow of visitors. But there is a way to solve this...

Read more

The Best Times to Visit a Hospital

What are the best times to visit a hospital? Your patients don't want to spend their time in long queues, so make your hospital a better place to visit.

Read more

Why Hospital Sign-In Sheets Are Not Effective

Many hospitals are still using sign-in forms for patient registration. Is there a good alternative to paper sign-in sheets? There is a time-saving way...

Read more

A Hume Makes Online & Offline Shopping Seamless

Customer service values that historically allowed them to compete against countless competitors. Is your business set up to fight for another century?

Read more

Using Queue Management System for Sales and Data

Using a Queue Management System can bring amazing sales insights and customer data. Learn how to use the software to bring results.

Read more

Why Do People Queue Before Boarding Flights

Why do people queue up before boarding flights? Airlines can manage waiting lines better for everyone.

Read more

Why It's Crucial To Greet Customers

The simplest and best way to increase sales is to greet every customer.

Read more

How does wireless queue management system work?

We explain how wireless waiting line and queue management systems work. Learn about waiting line management and customer experience management.

Read more

How to know if your pop up shop was a success

Get the retail metrics from technology to understand if your pop up shop was a success. From foot traffic to sales.

Read more

Web-Based Queue Management

Easy to use SaaS web-based queue management system by Qminder. No downloads, no software, easy for everyone.

Read more

Qminder Queue Management System Using Printer Tickets

Star Micronics AsuraCPRNT printers are supported by Qminder waiting line management system.

Read more

Easy Qminder Set Up with Bouncepad

Qminder queue management system recommends Bouncepad as a visitor sign in kiosk.

Read more

Where do people wait in South Korea?

Smartphone based queue management system lets you tell where you hate to wait, even in South Korea.

Read more

Why we are doing this?

Line waiting management solution Qminder is part of Seedcamp family. We do this to eliminate lines.

Read more

All is fair in love, war and Garage48

Qminder won Garage48. Here is our quick overview of Qminder's first 48 hours.

Read more

Hello, world! Starting a Queue Management System

Qminder queue management system is available to everybody. Because in the end, everybody freaking hates to wait.

Read more

startupnow - Insights from the 2011 Seedcamp teams

Qminder featured at StartupNow. Insights from the 2011 Seedcamp teams including GrabCAD.

Read more